COP25: The gap between actions and words—why Article 6 negotiations continue to stall

17 December 2019, Dr Jasmine Hyman, Category: All insights, News, Tags: adaptation, Adaptation Fund, Article 6, climate ambition, climate finance, Climate goals, COP, COP25, events, GDP, Glasgow, Greenpeace, Greta Thunberg, ITMOS, Kyto Protocol, Madrid, mitigation, NDC, Negotiations, Paris Agreement, SBSTA, Spain, UNFCCC, Yale

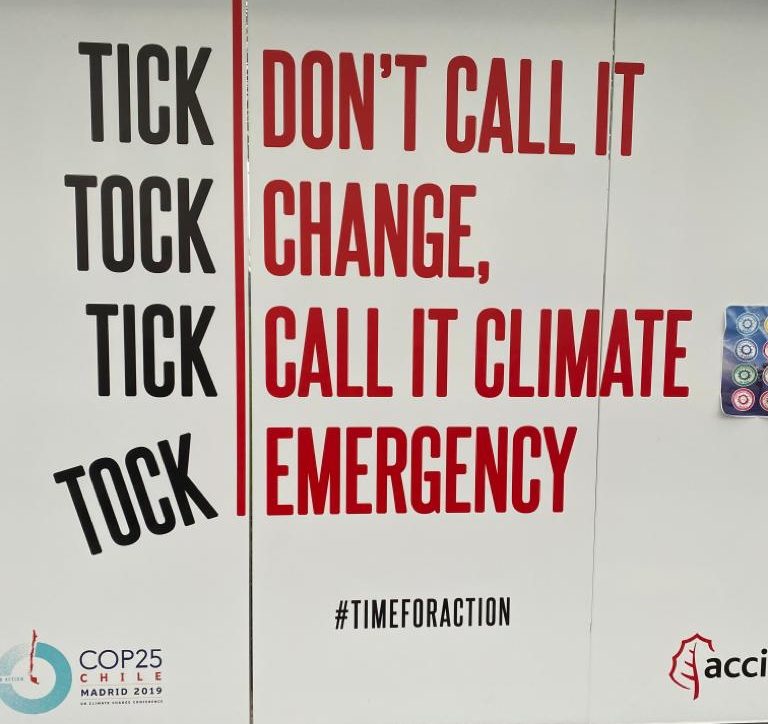

The 25th Conference of the Parties (COP 25) finally closed last Sunday at lunchtime in Madrid, making it the longest-running COP in history, and also one of the least effective climate negotiations ever. With over half a million Spaniards marching through the streets of Madrid on December 6th in a declaration of climate emergency, observers within the negotiation halls, E Co. staff among them, were disappointed by the intractability and lack of leadership in the plenary. Jennifer Morgan, Executive Director of Greenpeace, said “the gap between inside and outside has never been greater.”[1] All the same, I’m going to argue that no agreement on the key issue on the table—Article 6—might be better than a weak agreement.

E Co. attended COP as a chance to gauge the ambition and direction for the international climate funds in the year leading up to the communication of the Nationally Determined Contributions in 2020 (i.e. the climate actions each country will put on the table). Yet while there was a lot of talk about ambition, the actual work at hand was the operationalisation of Article 6, which is the only article in the Paris Agreement that still lacks rules for implementation. What makes Article 6 so tricky, and how does it inform our work at E Co. in project design?

Working within the Paris Agreement framework

Indigenous attendees pressuring world leaders to act faster on climate change. Photo credit by UNclimatechange Flickr

Article 6 is the article in the Paris Agreement that describes how countries can collaborate with one another in meeting their climate commitments. I remember the celebrations at the end of the COP 21 in Paris—people were crying with joy in the negotiation halls. And I remember feeling a little out of sync with these celebrations, because the Paris Agreement is based on bottom-up pledges and this meant, by definition, that comparison (and therefore coordinated collaboration) was going to be challenging. How would this all work?

Countries are all free to pledge their climate commitments in any way that makes sense to them: there can be performance standards, pledges to reduce the intensity of carbon intensity per unit of Gross Domestic Product, and there are also the rare and truly ambitious commitments to an absolute greenhouse gas cap against a baseline, though even here the baseline and the target dates are free for the country’s choosing. I think of the Paris Agreement as a type of poker game, where countries just put down on the table what they’re willing and most able to offer; my colleague Gediz Kaya and I wrote a guide for the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies on how to decrypt each country’s carbon hand at the end of the Paris negotiations, four years ago. Prior to Paris, negotiations often got bogged down by the principle of “common but differentiated responsibility” i.e. the idea that developed countries should do more than developing countries to save the planet.

The Paris Agreement sidesteps the old negotiation impasses by simply stating that everyone can just do what they want. China has submitted an intended Nationally Determined Contribution and so have Brazil and India. Large historic emitters, i.e. the United States, can no longer refuse to act because “China’s not doing their part”. The Paris Agreement asks all countries to take action, but in order to make that demand, it lets them do it in their own way. The Kyoto Protocol, on the other hand, defined a measurable unit (the assigned amount unit, or AAU), created an internationally coordinated framework for tracking climate action, and committed industrialized countries to reduce their emissions to approximately 5% below 1990 levels from 2008-2012. The agreement had clarity, but it failed to gain buy-in. In response, the Paris Agreement relies on voluntary pledges from everyone.

The Article 6 conundrum

Countries are increasingly being pressured to accelerate climate action

And this is the heart of the trouble with figuring out how to implement Article 6, which defines how countries will account for and coordinate their mitigation actions with their neighbors. The Paris decision nominated the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) to identify rules for its operationlisation, and these rules keep getting punted down the line. Paul Watkinson, head of the SBSTA for the UNFCCC, says that despite the challenges of Paris’ bottom up paradigm, “an inclusive approach was needed.”[2] He continues:

“Sometimes people think Article 6 is about global carbon markets, I don’t think it’s quite that. It’s about the way parties cooperate, and that includes markets. If parties are going to exchange carbon credits among them, then we need a way of tracking that is… robust, credible … ensuring environmental integrity and avoiding double counting.”[3]

Article 6.2 covers the modality and procedures for national collaboration in situations wherein a country exceeds its own targets and seeks to sell Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOS) to another country. Sticky issues include the high possibility of double counting or excessive counting (i.e. “hot air”) in a “pledge what you want, and how you want” agreement framework. The alternative possibility—creating strict rules and regulating the credibility of ITMOS, would require sufficient international ambition to form a rigorous agreement on what an ITMO should be.

Article 6.2 would inform Article 6.4, which is targeted at firms who could invest in emissions reductions projects, and for this reason it is often erroneously assumed to face similar difficulties faced by the Kyoto Protocol’s flexible market mechanisms under Article 17. Yet while the mechanism under 6.4 might be able to draw upon the lessons from operationalising Article 17, the demands of the Paris Agreement are now far more complex. The Article 6.4 mechanism must identify procedures for accountability and reporting for both developed and developing countries without a standardized emissions accounting unit, and without an overall cap on emissions reductions that can ensure that whatever market is created will actually reduce greenhouse gases. In order to address this basic issue: “are we just creating a business opportunity for emitters, or are we actually mitigating climate change?” there have been a series of ideas on how to restrict market supply: namely, a tax or a fee on transactions under 6.4 that would be transferred to the Adaptation Fund.

Threats to private sector engagement & E Co.’s role in driving climate ambition

Some business associations say that such a levy could kill private sector engagement. But at E Co, we want to see business drive ambitious climate mitigation and we could embrace a transaction fee for the Adaptation Fund because it would be both progressive (i.e. it would serve the most deserving populations) and it would also create a demand-driven market for emissions reductions that could help drive ambition. However, in order for such an idea to work there would need to be clear, long-term, policy signals from the UNFCCC. In our climate change project designs, we have noticed again and again that policy uncertainty deters investment much more dramatically than progressive price signals, which can be managed.

Conceptually, it is also unclear how 6.2 (coordination) and 6.4 (trading) will engage with one another. If a nation supports ITMOs in one country context, should there be a single accounting process to avoid double counting of ITMOS in their place of origination and their point of funding? Who gets the credit for the ITMO? [4]

At the core of the Article 6.2 and Article 6.4 discussions is a rather political issue: ambition

Greta Thunberg accused COP 25 of negotiating loopholes—she was speaking to the overarching view that if the negotiating blocs put climate change mitigation at the heart of the discussions (and not the cheapest way to look Paris compliant) then the standardization of the national pledges (i.e. Nationally Determined Contributions, or NDCs) and a clear accounting system for managing ITMOS would not be so hard because there would be a willingness to accept some international standards. COP 26 in Glasgow is slated to be a hallmark year for the climate negotiations, as this is the year when Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) ambitions will be raised and new commitments for climate finance will be made public. While disappointing to leave Madrid tired and empty-handed, an overly laden and complex interpretation of Article 6 would be devastating in the long-run—engendering an obscure and complicated trading system. The only useful way out of the Article 6 negotiations is an injection of serious goodwill from the negotiating blocs.

E Co. will do its part in the run-up to Glasgow by continuing to demonstrate that ambitious and rigorous climate change mitigation policy and project design is not only possible, it’s profitable. Waiting another year for Article 6 to mature just puts the negotiators under the pressure cooker of Glasgow, where activists and participants are expected to flood the negotiation arenas: political pressure must reach the tipping point before the climate does.

Bibliography

[1] Quoted within Carbon Brief’s “COP 25: Key Outcomes agreed at the UN Climate Talks in Madrid.”

[2] Interview with Paul Watkinson on Environmental Insights: Conversations on Policy and Practice from the Harvard Economics Program, by Professor Robert Stavins, December 10, 2019.

[3] Interview with Paul Watkinson on Environmental Insights: Conversations on Policy and Practice from the Harvard Economics Program, by Professor Robert Stavins, December 10, 2019.

[4] For further explanation, see Carbon Market watch, “Carbon markets 101: The Ultimate Guide to Global Offsetting Mechanisms.”

Did you attend COP25? Send us your thoughts regarding the state of negotiations to: amy@ecoltdgroup.com

Join the conversation by posting a comment below. You can either use your social account, by clicking on the corresponding icons or simply fill in the form below. All comments are moderated.