Applying climate finance to a blue economy approach

10 July 2023, Category: All insights, News, Tags: adaptation, blue economy, blue forest, climate change, climate finance, sustainable development

Healthy oceans and marine areas are sources of countless vital social and ecosystem services. Climate regulation, economic development, food security, biodiversity conservation – these are all provided by our coastal and marine environments. Globally, many communities rely on seas, coasts, and waterways as their primary location for food production and livelihoods.

Today, our oceans face a wide variety of man-made threats, such as biodiversity loss, ocean acidification, ocean warming, and pollution. Private and public sector actors are, therefore, being increasingly called to set targets for reaching successful environmental legislation across ocean and marine management, and create a level economic and legislative playing field that will benefit every nation that participates in it.

While the blue economy is an economic concept that will have marginally different applications within each scenario it finds itself championed and implemented, due to the varying nature of area-based and national considerations, there are several things that unite the blue economy:

- An understanding of it as a mechanism to simultaneously protect marine ecosystems while building economic development;

- Acknowledgement of past marine-based environmental regulation, and the process of building upon what has come before;

- An integration of the most up-to-date climate science and information;

- The utilisation of innovative climate finance mechanisms that can unite both public and private sources of funding.

What is the blue economy?

There are various definitions of the blue economy. In the World Bank’s ‘The Potential of the Blue Economy’ report, it is understood as ‘comprising the range of economic sectors and related policies that together determine whether the use of oceanic resources is sustainable’ [1]. A similar definition in another World Bank document is the ‘sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods and jobs, and ocean ecosystem health.’ [2].

At its core, the concept promotes the protection and improvement of marine-based livelihoods and the economic development of said livelihoods while simultaneously ensuring environmental protections. It is an acknowledgement of the complex and at times fragile state of oceanic systems and works to decouple environmental degradation from economic development.

This movement is not without its challenges. The main two obstacles to securing and growing the concept of the blue economy in actuality are:

- Properly and effectively understanding how to manage the countless aspects of coastal, marine, and oceanic sustainability.

- Ensuring transboundary, international collaboration from the many nation states that have either jurisdiction, dependence, or a vested interest in our oceans as the means to livelihood support and/or economic development. This also means uniting private and public interests across, quite frankly, every country on the planet – with an emphasis on providing for Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and Coastal Least Developed Countries (CLDC).

It can be roughly interpreted as the management of and relationships between six key sectors/mechanisms:

- Energy: The world’s oceans represent limitless potential for renewable energy production, and will play a vital role in sustainable economic development.

- Fisheries: Estimates by the FAO show that around 58.5 million people are employed worldwide in primary fish production alone [2]. In 2019, 3.3 billion people received 20% of their protein intake from aquatic sources [3]. An emphasis on creating more sustainable fisheries will help restore fish stocks and even generate increased revenue.

- Transport: Maritime trade routes represent that vast majority of international goods traded, with UNCTAD estimating this number as over 80% [4]

- Tourism: Coastal and marine tourism is a huge pull for the tourism sector, benefitting many local economies. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Small Island Developing States (SIDS) received 44 million inbound visitors [5].

- Climate change: Our consumption and use of fossil fuels is creating unprecedented changes within the global marine environment. For example, sea levels are rising, threatening the land and livelihoods of countless islands and coastal zones and communities.

- Waste management: One of the biggest challenges for marine environments and biodiversity is waste – in particular, plastic pollution. Better land-based waste management systems will help ocean areas to recover.

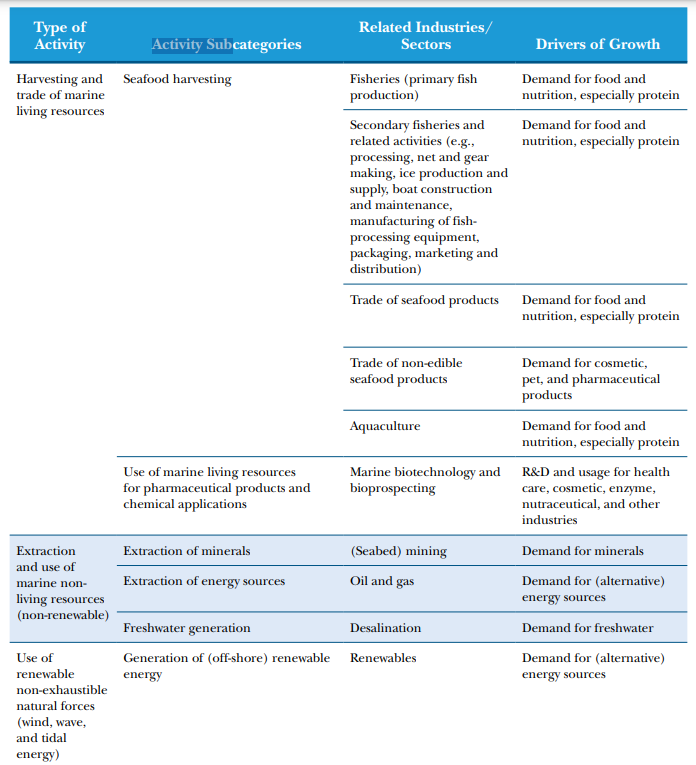

Figure 1. Examples of activities originating from marine ecosystem services and the drivers of growth in those activities (World Bank)

The current context

Ensuring a blue economy requires rules and regulations followed by countries worldwide. The blue economy is and always will be a concept which emphasises protections, sustainability, and support for SIDS and CLDC. Because of this, our marine regulations and legislation must work to centre these communities and ensure that the right protections are in place for the sustainable use of ocean resources.

Ocean protections have often been only referred to in small, implicit ways throughout the larger pieces of environmental legislation. Usually, due to the size and importance of our oceans, and the complexity of their care and management, coastal and marine ecosystems receive specifically dedicated pieces of legislation. For example, the Paris Agreement only contains one mention of oceans, found in the Preamble:

Noting the importance of ensuring the integrity of all ecosystems, including oceans, and the protection of biodiversity, recognized by some cultures as Mother Earth, and noting the importance for some of the concept of “climate justice”, when taking action to address climate change,

At COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, action on ocean protection and management was furthered in the CMA Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan (Decision 1/CMA.4) and COP Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan (Decision 1/CP.27). In paragraph 46 of Decision 1/CP.27, it reads:

Encourages Parties to consider, as appropriate, ocean-based action in their national climate goals and in the implementation of these goals, including but not limited to nationally determined contributions, long-term strategies and adaptation communications;

This sentiment is mirrored in 1/CMA.4. Also in 2023, delegates of the Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) signed the High Seas Treaty, which builds on the 1982 UNCLOS. This treaty is designed to better ensure protections and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas that sit outside of national jurisdictions. So, while coastal, inland, and EEZ waters are governed and regulated by national and transboundary bodies, the High Seas Treaty makes it simpler and easier for better economic regulation to be enacted in the spaces outside of national regulatory scope.

What does the blue economy need to work?

The blue economy must be fully integrated into the most up-to-date climate models and current Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) as set by the IPCC, in order to anticipate the impacts of both current and future climate impacts. In the specific case of ocean and marine-based economic systems, there are several impact vectors that can be focused on:

- Sea-level rise;

- Acidification;

- Changes in currents;

- Higher water temperatures;

- Biodiversity loss.

The issue is that these vectors are quite difficult to model in terms of severity and location. Additionally, the effects of each of these are different, and how they interplay will not be a constant and/or linear relationship across all circumstances in which they occur. So, at first, the blue economy needs to work on understanding the impacts, and use that understanding to alter and improve the approach of marine resource management.

So what else does a blue economy need?

- It needs to be low-carbon and clean;

- Any growth is driven by investments that actively reduce carbon emissions and/or pollution;

- Those investments should also go towards halting the loss of biodiversity;

- It needs recognitions of the unique national circumstances that each participating country experiences;

- It needs to account for the changes in regulation over particular maritime zones e.g waters under specific national sovereignty;

- It needs to account for issues related to both capacity and any unique environmental, social, and cultural conditions that may be at play.

The role of climate finance projects and programmes

Climate finance, alongside other public financing and other innovative financing mechanisms that can fund existing, new, or nascent sectors, has great potential for supporting blue economy strategies. However, pursuing a blue economy strategy requires not just a short-term injection of cash, but a long-term, affordable financing that can be applied at scale.

There are issues with this approach. As we’ve stated, it is SIDS and CLDCs that are most in need of the benefits of a blue economy, and yet these are usually the areas which have the least capacity to apply for funding. It should be the responsibility of both large climate funds, such as the Green Climate Fund and the Adaptation Fund, to spearhead easing access for these smaller nations and communities. Accredited Entities also have the responsibility of providing support for SIDS and CLDC, and championing their causes.

One of the key learnings from the application of climate finance projects and programmes is that by applying science-based integrated marine planning and removing barriers to sustainable development, we can not only correct policy and market failures, but also generate remarkable economic development in target areas. So what might these climate finance mechanisms look like in practice?

- Finance for government reform and ecosystem-based management have already seen funding come from sources such as the UNDP, FAO, the World Bank Group, and the multilateral climate fund, the Global Environment Facility (GEF).

- In smaller scenarios, we are currently seeing an increase in financing through marine conservation, alongside debt-for-nature swaps, which work by mobilising private impact investor resources which then are swapped for high-interest sovereign debt, in exchange for governmental commitments to adaptation and mitigation measures.

- We are also seeing an increased amount of blue bonds, which are new ‘blue’ versions of land-based green bond mechanisms. For example, the Seychelles are one of the first nations to trial blue bonds. Bonds are sold, with the facilitation of the World Bank and the African Development Bank (ADB), and the finance gained will be used to finance fisheries management.

A good example of the usefulness of climate finance in a blue economy approach is the current UNDP-GEF development of ocean and coastal market transformation techniques, such as the Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis/Strategic Action Programme, which allows participating countries to collaborate on addressing environmental or other common issues in share ecosystems.

One final thing to note is this; Public sources of finance are not enough to bring about adequate and fit-for-purpose blue economy mechanisms. Private capital will play an important role.

What are your thoughts on the role of climate finance, funds, and AEs within the development of the global blue economy? Email us at: amy@ecoltdgroup.com or find us at the following:

Twitter: @ecoltdnews

LinkedIn: E Co.

Instagram: @ecoltdnews

References

- https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/cee24b6c-2e2f-5579-b1a4-457011419425/content

- https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/infographic/2017/06/06/blue-economy

- https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/oceans-fisheries-and-coastal-economies

- https://www.fao.org/3/cc0461en/online/sofia/2022/consumption-of-aquatic-foods.html

- https://unctad.org/publication/review-maritime-transport-2021#:~:text=Maritime%20transport%20is%20the%20backbone,higher%20for%20most%20developing%20countries.

- https://www.aosis.org/sustainable-recovery-of-the-tourism-industry-at-the-sids-global-business-network-forum/

Join the conversation by posting a comment below. You can either use your social account, by clicking on the corresponding icons or simply fill in the form below. All comments are moderated.