News: Thoughts from CTCN Africa Forum and for country-led climate action

18 April 2019, Dr. Silvia Emili, Category: All insights, News, Tags: adaptation, Africa, climate change, climate technology, CTCN, energy access, mitigation, stakeholder engagement

7 minute read.

The role of participation and stakeholder engagement in accelerating access to climate technologies.

As part of my recent visit to West Africa, I attended the CTCN Regional Forum in Accra, Ghana. Organised as part of Africa Climate Week, the Regional Forum convened African National Designated Entities (NDEs) and some CTCN Network members, Nationally Designated Authorities to the Green Climate Fund (GCF), representatives of financial institutions and other government officials. The CTCN mandate is to help countries meet their national climate change commitments through technology assistance, capacity building programmes and knowledge sharing initiatives. CTCN works on a country-driven and demand-driven basis and it supports 160 NDEs to accelerate and complete the transfer of climate technologies.

The aim of this forum was to strengthen the regional network of NDEs, share the latest CTCN initiatives in regard to technical assistance and other services, as well as to identify country needs and priorities and future opportunities for CTCN’s support. It was organised over two days of productive discussions, knowledge exchange activities and presentations about NDE engagement with the CTCN and Network members, where I had the opportunity to share our lessons learnt from working in the region.

Here are some of my key event takeaways and some entry points for accelerating access to climate technologies, looking particularly at the role that stakeholder participation and designing for access can play in achieving this goal:

Key takeaways from the CTCN Forum

The forum opened with an overview of the achievements of CTCN since its establishment five years ago: 137 technology projects supported, of those 54% were mitigation projects, 32% adaptation and 14% a mix.

The first session explored in depth the Technology Framework of the COP which is based on five themes: innovation, implementation, enabling environment and capacity building, collaboration and stakeholder engagement support. The debate revolved mainly around innovation, and participants raised concerns about the definition of the term (i.e. is it only technological or also business innovation) and what does that entail when applied in different contexts? Some of the questions raised were concerning innovations at different stages of value chains, and the relationships between innovation and inclusive growth. NDEs shared their valuable perspectives and suggestions for informing the COP process. For instance, the representative from Kenya stressed that there is a need to incorporate indigenous knowledge, particularly for adaptation to climate change, and that innovative existing technologies and capacities need to be further integrated in technical assistance processes.

Another interesting discussion revolved around the importance of exchanging perspectives and experiences at the regional level. The representative from Congo stated that, “It is crucial to facilitate knowledge sharing among NDEs and among countries for South-South cooperation”, and many NDEs shared similar issues. These include coordinating with the other climate focal points, engaging with the private sector and relevant stakeholders, and understanding and accessing climate finance mechanisms.

One of my key takeaways was recognising the urgent need to support integration between climate focal points (technical and financial) at the country level in order to avoid inefficiencies and duplication of projects, and to accelerate technology transfer. The forum provided a number of opportunities for discussion around the need to strengthen collaboration between technology and finance mechanisms as a key to maximise climate initiatives.

Collaboration, participation and meaningful stakeholder engagement

The CTCN Forum served to facilitate a fruitful exchange of ideas and demonstrated to be an important platform to better understand country priorities and struggles in accelerating access to climate technologies. In this context, the importance of stakeholder engagement and meaningful participation by country representatives and potential beneficiaries appeared to be a recurring need in order to strengthen collaboration and deliver climate action at the local level.

When talking about accessing climate finance for mitigation and adaptation projects, the importance of engaging with country stakeholders and adopting participatory processes in project design is often underestimated or misunderstood. While all climate finance mechanisms request demonstration of country ownership and embedding, participation of local stakeholders and beneficiaries is too often overlooked. Our 10th GCF insight on Stakeholder Engagement has revealed that in many cases, project design processes do not include beneficiary engagement from the start of project preparation, but it rather allows this to evolve or be driven by the host country.

Even when stakeholder engagement is undertaken during project development, participation of communities and local stakeholders is not necessarily a recipe for greater inclusion and may even have rebound effects. As Robert Chambers, a leading development academic who has worked on participation and development for several decades, observed “Participation is an obvious prescription to overcome elite capture but is far from a magic wand. Who participates? Participation can itself be captured to become an instrument for exclusion of those who are meant to benefit, even to the extent of leaving them relatively worse off than before.”

At E Co. we adopt different strategies and methods during project formulation to ensure that the voices of those who should benefit from climate finance are involved at all stages of the design process. Below, you can see some examples of how stakeholder participation can be designed and implemented, and how the principle of designing for access can be streamlined throughout mitigation and adaptation projects and programmes:

Examples of stakeholder engagement and designing for access

- Consulting with potential beneficiaries during project design

While preparing a feasibility study for a GCF proposal preparation, I travelled to Western Tanzania to consult with local stakeholders and potential beneficiaries about their needs and priorities and to get feedback on the proposed interventions.

Focus groups and interviews were organised in villages surrounding refugee camps, where the local population has been affected by the changing climate and by the influx of large refugee populations. For this project, I developed a participatory approach for assessing vulnerabilities and needs of people and for capturing their views on the project design. The first step involved looking at establishing a baseline through warm-up exercises that would help us to understand people’s perceptions about climate change and their coping mechanisms. Then we determined openness and buy-in for potential interventions, asking them to identify potential locations and choosing appropriate technologies, such as water pumps or the provision of agricultural inputs and animal husbandry.

The project was then designed around existing saving associations that are going to be used to disburse funding at the local level, enabling communities to choose adaptation strategies and technologies that fit with their needs and priorities, and using a market-based approach to disburse grant funding in the communities. The project would also involve participatory village land-use planning as a mean to ensure meaningful participation of communities in decision-making about their own natural resources.

- Design inclusive business models

This example illustrates how climate solutions can be designed to include potential beneficiaries, in this case refugees, within business models themselves, which can be designed for inclusivity and for enhancing participation of marginalised communities.

We conducted a landscape study for the Moving Energy Initiative, an initiative funded by DFID which looks at demonstrating how innovative policy and practice can improve access to sustainable energy among displaced populations.

For this study, we collected primary and secondary data to identify changes in perceptions and drivers for private sectors to engage in humanitarian settings, as well as the business models used for a number of technologies. New business models have emerged that reflect the private sector’s new perspective on displaced communities. Firstly, refugees are no longer perceived passive recipients of aid but instead as potential customers and employees. Secondly, it follows that private sector respondents have shifted their approach towards refugees, moving from ad-hoc procurements towards market-oriented distribution models. Third, the interviews’ results indicated a change in the appetite and drivers of private sector companies, from a push towards Corporate Social Responsibility to the pull of engaging with displaced populations as part of their core business strategy. In this context, great opportunities lie in scaling-up these successful and inclusive business models, and in sharing lessons learnt so that the private sector can successfully implement new approaches of doing business with the most marginalised.

- Direct access to investment decision-making at the local level

Climate finance often follows traditional models of development funding, where communities have little or no say in the way money gets used at the local level. In most cases, communities are simply consulted about their needs. They don’t fully participate in decision-making processes on priority areas for investments and this may result in loss of local knowledge and may also translate into low adoption of solutions.

Building upon the successful results of the DFID-funded BRACED project in Mali, which implemented 48 resilience investments valued at over £ 1.9 million, benefiting 410,057 people with a number of adaptation technologies, we have been involved in supporting IIED and NEF in designing a GCF project that builds on the decentralised climate finance mechanism. This project will revolve around community committees that are formed and provided with capacity building to understand climate risks, assess adaptation options and ultimately prioritised investments decisions. These investments are then implemented by the local government in collaboration with civil society organisations and under community committees’ oversight.

A recipe for accelerating climate technology transfer: the participation ladder

These case studies serve as examples of how meaningful stakeholder engagement and appropriate project and business model design can be used to channel climate finance towards those who need the most while at the same time opening opportunities for country-led development.

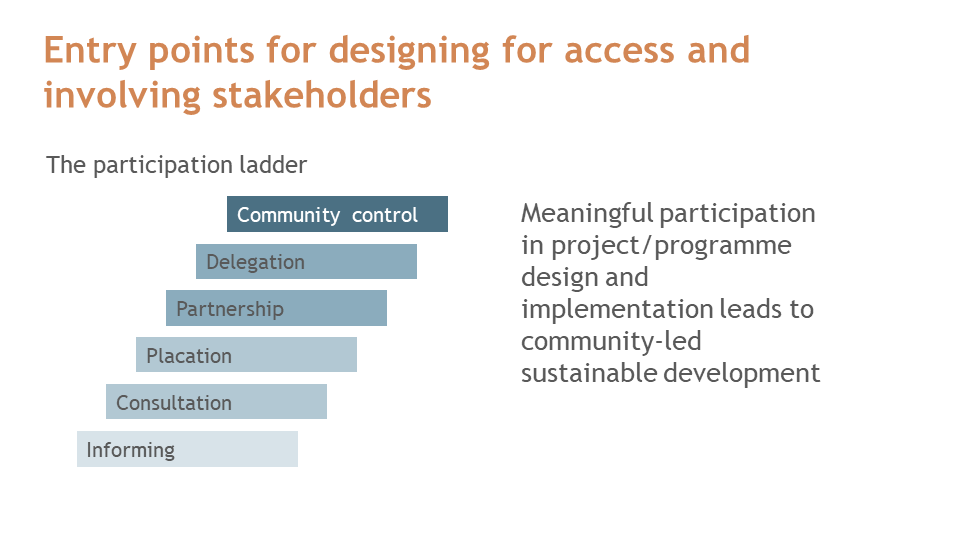

To better understand how different ways of engaging stakeholders affect power dynamics, we can look at these processes using the participation ladder:

Informing usually involves one-way flow of information and people have little opportunities to influence a project or programmed designed for “their benefit”. Consultation, is a step further, and using qualitative methods such as focus groups rather than surveys has proven to be a good way to collect feedback at the early stages of project design. Placation involves having some selected representatives to sit at the decision-making table. The degree to which they are actually placated, of course, depends largely on two factors: the quality of technical assistance they have in articulating their priorities; and the extent to which the community has been organised to press for those priorities.

Moving up to the ladder, power gets redistributed between communities and power holders, either through partnerships where planning and decision-making responsibilities are shared, delegation, where people have a dominant decision-making authority, and ultimately community control, where final decisions are in the hands of the communities themselves.

The strategies illustrated through these examples have the common goal of enabling communities to be their own actors of change, to increase their adaptive capacity by strengthening their decision-making power and ultimately increasing their resilience to climate change.

Did you find this article useful? Yes 🙂 No 🙁

Have you read Silvia’s last article on the 5th ARE Energy Access Investment forum?

Join the conversation by posting a comment below. You can either use your social account, by clicking on the corresponding icons or simply fill in the form below. All comments are moderated.